Prepping myself for this event this week. Gonna talk about the male gaze in live action, anime, and video games, not really about literature :).

Prepping myself for this event this week. Gonna talk about the male gaze in live action, anime, and video games, not really about literature :).

This post is based on my observation during the recent mass protests in Indonesia and I am more than happy to be proven wrong.

As I was intently following news and updates about the recent mass protests in Indonesia, especially after the death of Affan Kurniawan, I noticed something that makes me question the independence of the current Indonesian indie games scene.

As thousands of people went to the streets and had violent clash with the police, many Indonesian netizens voiced their support for the mass protests on various social media platforms like Instagram and Facebook. Many celebrities, influencers, musicians, and academia also publicly expressed their support for the protests, some in fact joined the protests on the streets. Yet, it was all strangely quiet in the Indonesian indie game network that I have been following. This silence is deafening, considering how justified and widespread the protests were.

Now, people may say that Indonesian video games are not political (yet) and should not be. But I will challenge this kind of perception. Video games have always been imbricated with politics, directly or indirectly. And Indonesian video games are not the exception here. From the first video games ban during Suharto’s New Order regime as part of its effort for total media control in 1981, to the creation of nationalistic video games such as Nusantara Online in the 2000s, to the “fatwa haram” of PUBG by MUI in 2019, to the successful participation of Indonesian eSports teams in SEA Games 2025, or the potential ban on Roblox over “immoral” content recently, all are evidence of how the production, circulation, and consumption of video games in Indonesia have always intertwined with politics.

Perhaps, one of the clearest paths to see the connections between Indonesian indie games and political events such as elections and protests is through the framework of newsgames, a term that refers to a broad body of work produced at the intersection of video games and journalism (Bogost, Ferrari, Schweizer, 2010), which is also part of my current research. In their book, Bogost, Ferrari, and Schweizer offer a category of current event newsgames as one type of newsgames, which for them mean games that are “short, bite-sized works, usually embedded in Web sites, used to convey small bits of news information or opinion [about current events]. They are the newsgame equivalent of an article or column.” One of their examples of current event newsgames is Gonzalo Frasca’s September 12th, a commentary on Bush administration’s war on terror military action after 9/11, which is a haunting and introspective current event newsgame.

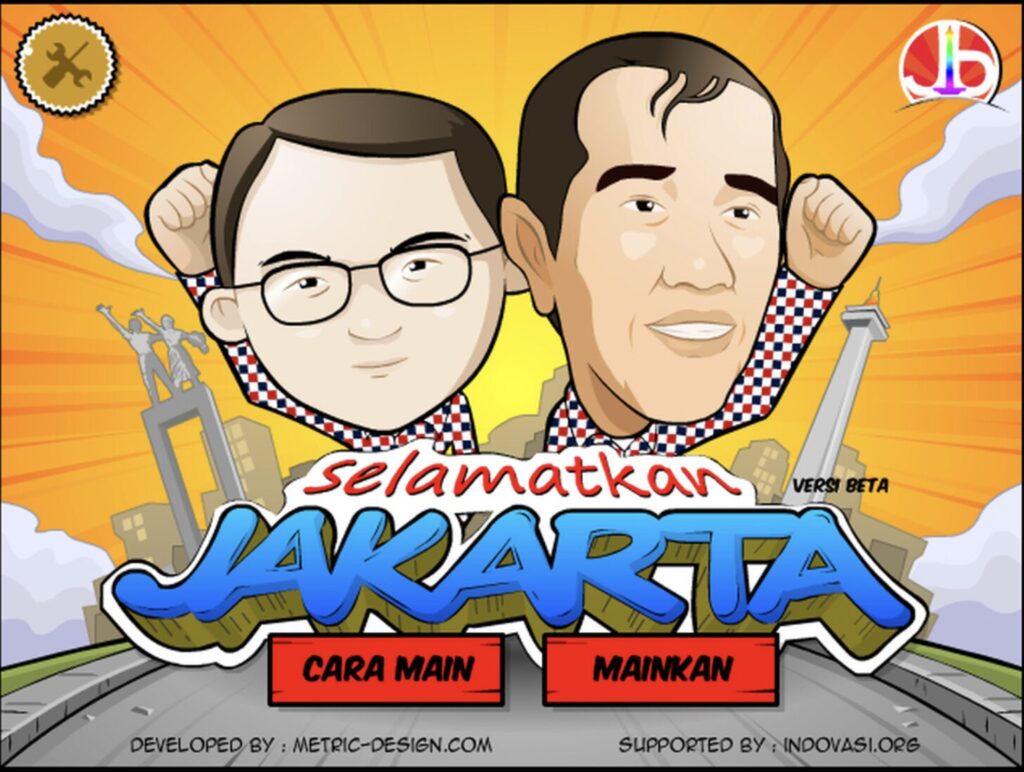

In the case of Indonesia, the production of current event newsgames perhaps can be traced to the Jakarta gubernatorial election in 2012 when Juwanda, a game developer from an indie game company in Bandung, Metric Design, made an Angry Birds-like game, titled Selamatkan Jakarta as his expression of support for Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok)’s gubernatorial run.

Afterwards, many indie game developers were involved in making current event newsgames related to political campaigns, such as Jokowi Go by Generasi Optimis and Prabowo the Asian Tiger by Sumarson, which were part of the 2014 presidential campaign.

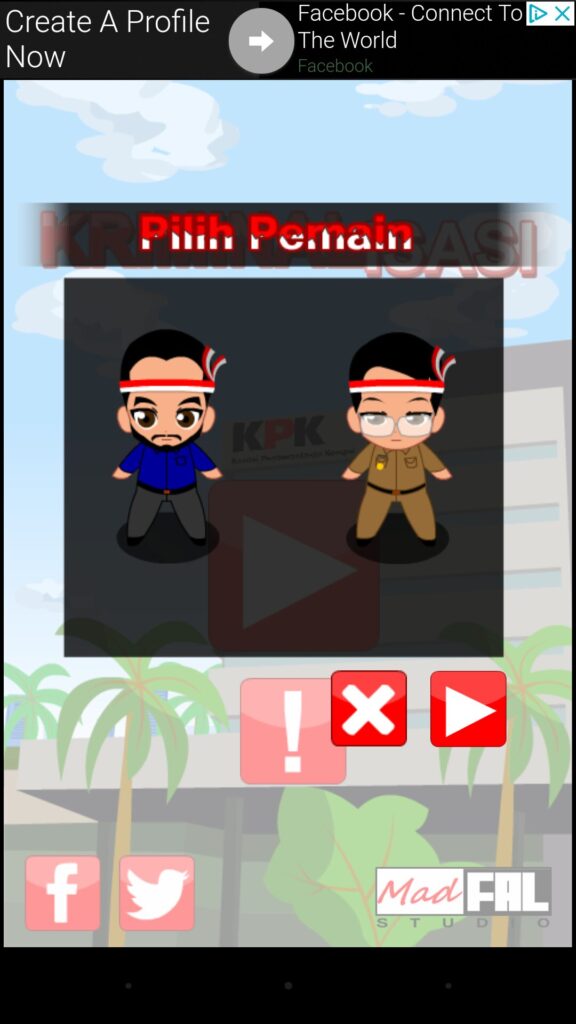

Another example of Indonesian current event newsgame that has a different tone is the game Kriminalisasi, wich was first released in 2015 by a one-man indie game studio, Madfal Studio, as a reaction to the criminalization of some officials in the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). It can be seen as a part of the “Save KPK” social movement in that year. The game used the then director of KPK, Abraham Samad, as its character, and later on also included Ahok, which was then the Governor of Jakarta, as one of its playable character.

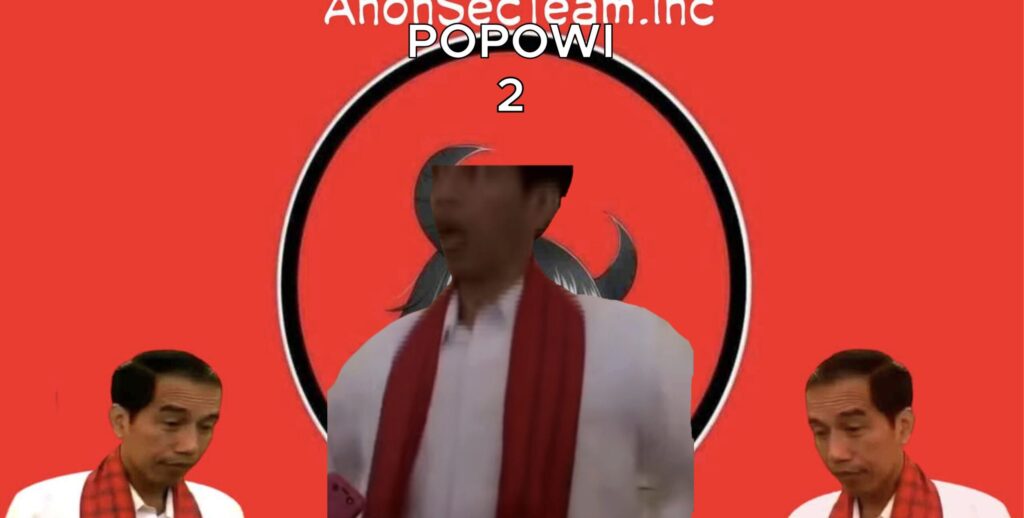

Perhaps the most controversial current event newsgame in Indonesia is the game Popowi, a meme game that was viral in 2021 as an editorial newsgame. This game, which was a clone of a popular meme game, Popcat, functions as a sharp-but-funny critique towards then-President Jokowi for his seemingly “surprised” reactions toward many controversies surrounding his administration and policies at the time.

Looking back to this history of Indonesian current event newsgames, I was somewhat disappointed to not see one popped out during the current mass protests, especially since Indonesian indie games scene has been experiencing somewhat of a renaissance in the last several years.

To a certain extent, I could understand the silent reaction in the Indonesian indie games scene toward the mass protests, especially among indie game developers and studios. I suspect that some of them, if not most of them, perhaps were supportive of the issues brought up by the mass protests. Yet, they could not publicly express it for fear of being targeted by the current government. This is because, in my observation, the proliferation of many indie games in Indonesia are tied to the support by government bodies, especially Ministry of Creative Economy (Ekraf/Bekraf) and Ministry of Communication and Digital Affairs (Komdigi). These two state institutions have been the main supporters in the development of Indonesian video game industry for several years now that I assume there is a strong reliance on their support among the Indonesian indie game developers. If in the US, video games are a part of military-entertainment complex, I would call what happens with indie games scene in Indonesia a form of state apparatus-entertainment complex. And this is why I am questioning its independence.

When you rely too much on the support of state apparatuses like Ekraf and Komdigi, you risk losing your freedom of expression and turning into their ideological mouthpiece. And I really hate to see it happen to the Indonesian indie games scene.

Here, I am reminded of a statement made by Merlyna Lim, an Indonesian media scholar whom I deeply respect, regarding Indonesian scholar’s responsibility in relation to the recent mass protests, which I think also applies in the case of the Indonesian indie games scene. I am quoting her statement here:

“Silence in these contexts is not simply absence—it is a stance, one that is recorded and noticed, and can be read as complicity… This silence raises a pressing question: what is the reason behind it?…Silence from privilege is not apolitical, it is a refusal of responsibility. In a world where the boundaries between scholarship and public life are increasingly collapsed, moral clarity is not only defensible but necessary. It makes us better researchers, more honest citizens, and more accountable human beings.”

Also, for those of you who are not familiar with the recent mass protest in Indonesia, you can also check out her timeline of the protests here to understand it.

Powered by WordPress & Theme by Anders Norén